My (Long) Road to an ERC Consolidator Grant (2019)

I am a botanist working on tropical rainforest evolution. While I won’t dive into the specifics of my research here, I aim to keep this blog as general as possible. I want to share my ERC journey, offering tips that worked for me and debunking some myths at various stages. I’ll skip the formal and technical details about the application process or oral exam since those are well-documented elsewhere. Instead, here’s my key takeaway: have a great idea, believe in it, and prepare rigorously. Leave nothing to chance.

As a young researcher or PhD student, ERC grants felt like an unattainable goal. The idea of applying for €1.5–2.5 million, crafting an ambitious project, convincing a panel of top experts, competing with peers, and passing an oral exam was intimidating, to say the least. But, like many daunting tasks, once you create your “ERC folder” and commit to it, anything becomes possible.

A Bit About My Academic Background

Before applying for the ERC, I secured a few mid-level grants related to my research, ranging from €40,000 to €300,000. One of these, the ANR Jeune Chercheur, took me four attempts to obtain—but that’s another story. These grants helped me build a solid publication record and carve out a niche in my field.

Do I Have a Shot at an ERC Grant?

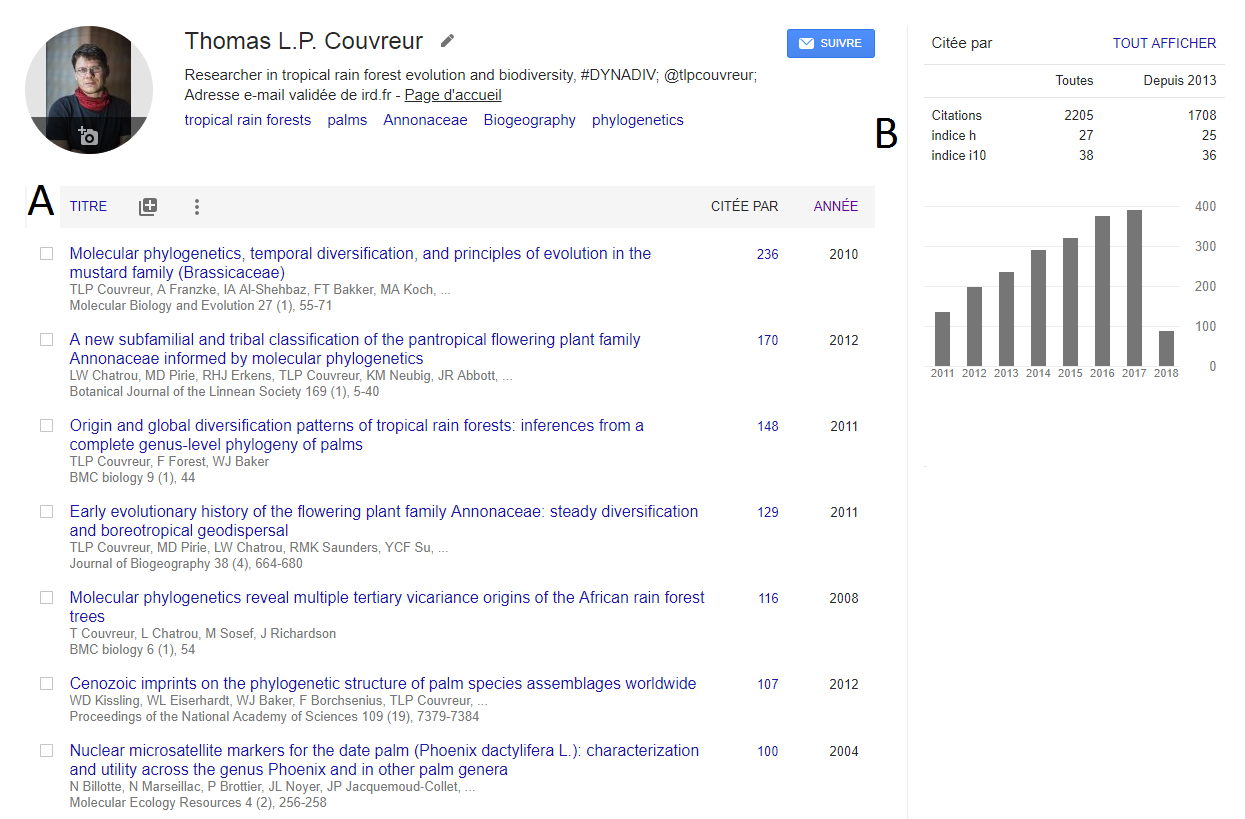

When I applied, my Google Scholar profile didn’t feature publications in Science, Nature, PNAS, or PLoS Biology—the top journals in my field. However, I had several well-cited articles (+100 citations each), and my annual citation count was steadily increasing.

The first myth to bust is this: you don’t necessarily need a publication in a top journal to apply for an ERC grant. While such publications might help, what matters most is being recognized as a leader in your field (in Europe) and having significant, supervisor-independent publications.

These earlier projects also helped me develop the tools and preliminary data needed to convince the ERC panel that my ambitious project was feasible—even if it sounded audacious. Another myth: you don’t need to have your ERC project in mind from the start of your career. My project idea emerged gradually as I completed other research and realized its feasibility.

That said, I wouldn’t recommend applying if you don’t have at least some preliminary data showing your idea’s potential. While ERC projects are high risk/high gain, they still need a solid foundation. Part of your proposal can venture into uncharted territory without preliminary data, but not all of it.

Going Beyond the State of the Art

Your project must be scientifically significant, groundbreaking, and beyond the current state of the art—something you’ll hear repeatedly during the process. This can seem obvious, but it’s a challenging concept to communicate effectively. Convincing your peers (and anyone else) that your project truly pushes boundaries is hard work.

When I first pitched my idea to colleagues (many outside my field), their reactions weren’t encouraging. They didn’t say, “Wow, Thomas, what a fantastic project—go for it!” Instead, I heard things like, “You know ERCs are competitive, and you need to go beyond the state of the art?” To me, that translated as: “Meh... not that interesting. You probably have no chance.”

Rather than feeling discouraged, I used their feedback to refine how I thought about and presented my project. Talking to colleagues and working groups early on was crucial. If they weren’t convinced, it was because I wasn’t pitching it clearly or persuasively enough.

This clarity is especially vital for the oral exam if you make it that far. Remember: it’s not enough to believe your project is great—you need others to see it too.

Another Myth Buster: Local Funding vs. ERC Success

A common myth is that rejection by a local funding body for a similar project means you’re unlikely to succeed with an ERC application. This is complete nonsense. The ERC grant system is fundamentally different: it’s larger in scope, involves a multi-part project structure, an oral exam, and an international panel.

Take my case as an example: my ERC project was rejected 3–4 times at the local funding level but was accepted on my first attempt with the ERC. I also know of another case where the same thing happened. The ERC panel can see potential in a project that a local panel might not. The two systems assess projects very differently.

What Really Matters for an ERC Application

Besides the essentials I mentioned earlier, not much else on your CV holds significant weight—things like awards, promotions, or invited talks. Personally, I was invited to give only two seminars before applying. The focus boils down to:

- Prove you’re a leader in your field.

- Have a groundbreaking project.

- Demonstrate that you’re the only (or best) researcher to carry it out.

Once you decide to apply, commit fully—give it 150%.

How Long Do You Need to Write an ERC Proposal?

People often say you need at least six months to prepare an ERC application. While I agree in principle, it really depends on your starting point. I decided to apply just 2.5 months before the deadline. However, the project I submitted had been in development for two years as I pursued local French funding (e.g., ANR grants). While my ERC proposal was almost entirely rewritten from the earlier drafts, I already had a strong foundation to build on.

Once I committed, I informed my institution, and they were incredibly supportive. They helped with the budget, administrative tasks, and oral exam preparation, freeing me to focus on the science.

Why the ERC Stands Out

One of the most liberating aspects of the ERC (at least in my LS8 panel) is its exclusive focus on fundamental science. There’s no requirement for a public impact section, EU developmental goals, or major social objectives. While it’s a good idea to show relevance to Europe in general, the focus remains on the science.

The Proposal Documents: B1 and B2

The ERC application requires two documents:

- B1 (5 pages when I applied): The pre-proposal.

- B2 (15 pages when I applied): The full proposal.

Both must be submitted at the same time. Here’s the catch: only the B1 and your CV are considered in the first step. If your B1 doesn’t impress, the B2 might never even be read. This can be frustrating, especially after spending significant time on the B2.

However, writing both simultaneously has its advantages. They are complementary, and working on them together makes the process more dynamic. The B2 provides the depth and specificity, while the B1 offers the clarity and appeal to a broader audience.

How to Approach Writing B1 and B2

Start with the B2. This is where you lay out the specifics—how your project will achieve its ambitious goals. The B2 keeps you grounded in reality, ensuring that your claims in B1 are achievable.

Once the B2 is solid, build your B1. This document is like your CV for the project—it needs to be clear, concise, and compelling. Think of it as your “hook” to the committee, enticing them to learn more. However, don’t overpromise. The B1 should say what you’ll achieve (“I shall do X, which has never been done before”), while the B2 should detail how you’ll achieve it. If you can’t explain the “how” in the B2, then it likely doesn’t belong in the B1.

In the end, the dynamic between B1 and B2 strengthens both documents. The B1 appeals broadly and draws interest, while the B2 provides the concrete evidence needed to convince the reviewers.

Perfecting Your ERC Proposal: Tips and Lessons Learned

Both the B1 and B2 documents must be as perfect as you can make them. Beyond focusing on the project fundamentals—state of the art, methods, timeline, and budget—you need to allocate significant time to perfecting every sentence, paragraph, and section. It’s not just about having a great idea; it’s about presenting it in the clearest and most compelling way possible.

Write, Revise, and Re-Read

I cannot stress enough the importance of revising your proposal repeatedly. I recommend reading “Writing Science: How to Write Papers That Get Cited and Proposals That Get Funded” by Joshua Schimel. This book has been incredibly helpful for me over the years, especially for grant writing. While there are many other excellent resources, Schimel’s advice consistently hit the mark for me.

Remember: don’t leave anything to luck, especially in how you write. Poorly constructed sentences, confusing explanations, or avoidable errors can harm your chances of progressing. Once you’ve laid down your great idea, dedicate significant time to refining your text. For me, this meant long days of writing and revising, starting at 5–6 a.m. and finishing around 5–6 p.m.

Finding Motivation During the Writing Process

Oddly enough, I truly enjoyed writing my ERC proposal. It became a chance to design my dream project with full institutional support (something I recognize not everyone has). I found myself learning new things, reading cutting-edge research, and getting excited about the science.

One unconventional tip: find something that pumps you up while writing. For me, it was listening to motivating music—like an athlete preparing for a competition. It may sound silly, but it really helps to get into the zone!

Bounce Ideas Off Others

A key part of my writing process was having someone to act as an “idea bouncer.” My postdoc, Andrew Helmstetter, filled this role perfectly. I would pitch ideas to him, and he would give honest feedback on whether they were interesting, correct, and feasible. Andrew also reviewed my timelines (chronograms) to ensure they were realistic, given his experience with similar analyses.

If you don’t already have an “idea bouncer,” find one. This could be a colleague, student, or anyone interested in your project. Their feedback will help you ensure your proposal is coherent and well-structured.

For my B2 draft, Andrew was the only person who read it in full and provided detailed feedback. However, I shared drafts of my B1 with several people, including past ERC grantees, who offered valuable insights. Aim to share your drafts widely—constructive criticism is essential for improvement.

Preparing for Submission

Plan to finish both the B1 and B2 at least a week before the deadline. This leaves time for polishing without last-minute stress. Take a two-day break from the project before your final review. This break helps you return to it with fresh eyes.

In the last few days, read the entire proposal aloud. Yes, aloud! This has two major benefits:

- Spotting Errors: Reading aloud forces you to notice every word, helping you catch missing words, awkward sentences, or formatting issues (like copy-paste errors).

- Post-Submission Peace of Mind: Knowing you’ve thoroughly reviewed every detail will reduce anxiety about potential mistakes after submission.

Maximizing Writing Time

Writing an ERC proposal demands time and focus. For me, this meant starting in mid-November and working steadily through early February, balancing this with holiday breaks and other commitments. Here are some strategies that helped me carve out time:

- Say “No” to Non-Essential Tasks: I declined review requests and non-urgent commitments.

- Use an Email Autoresponder: My out-of-office message explained that I might not reply promptly due to grant writing.

- Work from Home: For maximum efficiency, I worked from home two days a week whenever possible.

- Prioritize Critical Tasks: I made time for students and article revisions but minimized other distractions.

By focusing intensely on the proposal, I was able to dedicate the time and attention it required.

Final Thoughts

Writing an ERC proposal is demanding but incredibly rewarding. If you approach it with commitment and passion, the process itself can be enjoyable and inspiring. Remember, this is your chance to design your dream project—make it count!

Once you've submitted your proposal, life gradually returns to normal. As I mentioned earlier, the writing process was both exciting and rewarding. It provided the opportunity to dive deep into the literature and engage in fascinating discussions, making the experience worthwhile.

Then came the day when I received an email announcing that my proposal had passed the first round and that I was invited for an interview. This was a significant milestone. It meant that my grant proposal (B2) would be fully evaluated, and the initial application (B1) had done its job. I now knew that the committee was interested in my project, and no matter the outcome, I had a real chance of securing the funding.

Preparation for the Oral Exam:

(2024 update: this might be outdated because of COVID since the exams were on zoom, but still the overall preparation would be the same)

The email arrived on June 26th, and my oral exam was scheduled for early October, giving me three months to prepare. The oral exam is intense—you have only 10 minutes to convince a panel of experts to fund a €2 million project. That's €3,333 per second!

In this section, I'll share a few tips that helped me throughout the preparation process, focusing on the training aspect rather than the content or structure of the presentation (as you likely know your project best).

As a scientist, I’ve always believed that oral presentations are just as important as the science behind them. The ability to present effectively, not just the science but the structure and delivery of your ideas, can significantly impact your career. I’ve spent a lot of time refining my presentation skills, studying everything from slide design to voice modulation. For the ERC, I knew I needed to deliver a near-perfect presentation.

I decided to write down my speech, carefully choosing every word. While I typically don’t use a script for presentations, this time I felt that every word mattered. The text evolved over time as I continuously refined the phrasing.

Here are a few tips that helped me in my preparation:

- Practice, practice, practice: I rehearsed my speech multiple times a day, especially in the month leading up to the exam. By the end, I was rehearsing almost constantly. The goal was to learn the speech well enough to deliver it as if I weren’t reading from a script.

- Rehearse in varied settings: I practiced in different environments, from home to outdoor spaces, to simulate presenting in front of an audience. The more diverse the settings, the better I became at handling distractions and unexpected situations. I even had my child distract me during rehearsals to add a layer of challenge.

- Start from different points: To avoid being dependent on memorizing the speech from the beginning, I practiced starting from various points. This helped me become more flexible and less predictable.

- Visualize: A particularly effective technique was closing my eyes and visualizing the slides while saying my text as quickly as possible, without mistakes. This helped me internalize the flow and get comfortable with the material.

- Engage with TED Talks: I found TED Talks to be an invaluable resource. Listening to top-quality talks helped me refine my own delivery. I listened to as many as I could, paying attention to tone, structure, and how ideas were pitched. You can even listen to the audio without watching the video, which makes it easy to incorporate into your daily routine.

- Master eye contact: Effective communication begins with eye contact. During my presentation, I made a point of looking at all committee members—not just one. This required me to learn my speech well enough that I could present without constantly relying on the slides. A relaxed face and slight smile were also essential to convey confidence and engagement.

- Practice in front of different people: The more people you present to, the more feedback you’ll get. I sought input from colleagues, and with tools like Zoom and Skype, I was able to practice presentations in short, focused sessions with people from various backgrounds.

- Attend ERC oral training (if possible): I was fortunate that my institution funded my participation in a two-day ERC consolidator training. This was invaluable as it allowed me to see how other candidates prepared and presented their ideas. It was particularly helpful for candidates who are not naturally comfortable with public speaking.

By the time of the oral exam, I felt prepared and confident. I knew the material inside out, and I had practiced enough to present it with ease and conviction.

As part of my preparation, I attended a mock ERC interview organized by Aviesan in France. The panel consisted of ERC laureates in my field, which made the experience incredibly valuable, particularly when it came to handling questions. It was an excellent opportunity to practice in a real-world scenario, allowing me to gain insight into how the actual interview might unfold.

Finalizing Your Presentation:

I finalized my presentation four days before the big day. It’s important to submit a printed version of your presentation before the interview, so I made sure everything was ready ahead of time to avoid any last-minute stress. Once your presentation is submitted, you can no longer make changes, which is actually a good thing. From that point on, you should focus entirely on delivering your speech with confidence and ease.

The goal of the oral exam is not only to showcase your project but also to present yourself as a confident researcher. The committee needs to feel that you are knowledgeable and at ease discussing your work. The preparation tips I shared will help you master your presentation so that you can appear calm, collected, and confident.

Answering Questions:

Once the presentation was finished, the questions began! There's no real secret to answering questions, but a few key strategies can make all the difference: be concise, honest, precise, and anticipate some typical questions. I won't go over the typical questions here, as you can find these in other resources or training courses. I started with a simple, straightforward "No" to the first question, which I think the panel appreciated for its clarity.

I got a mix of expected and unexpected questions. One of the expected ones was about why I believe my project is groundbreaking. I had prepared for this and had three key points ready to explain. I also received more technical questions, like "What does this theory mean?" or "Can you explain this fact?" It’s important to be able to explain complex ideas in clear, simple terms. My previous experience interacting with the press and the general public (radio, newspapers, public talks, etc.) helped me here. Even though the panel members are top-tier scientists, they may not always be familiar with the specifics of your domain, so making your explanations accessible is essential.

I had also prepared for questions related to the methods and the feasibility of my project, and these were among the questions I expected. A good tip for answering questions is to review your proposal and, for each statement or section, think about the potential questions the panel might ask. Practice answering those questions, either with a colleague or by simulating the scenario yourself. It’s useful to write down the questions and then practice answering them, as this can help you prepare mentally and come up with clear, concise answers when the time comes. (2024 update: One excellent source now a days is to use AI like notebookLM. You can upload your project and a bunch of important articles and then ask AI to generate questions…).

After the Questions:

Once the 15-minute question period ended, the panel president thanked me, and I thanked them in return. I left the room feeling good about how it went. I had answered all the questions without hesitation, and I had a strong feeling (just a gut feeling) that the panel was satisfied with my responses. Afterward, I quickly messaged my family and colleagues to update them on how the interview went. I took a moment to relax and unwind afterward—it's a huge relief once the presentation and questions are over.

The Waiting Game:

Then came the long and stressful wait. It took about four weeks to hear back. In the meantime, the panel sent me the reviewers’ comments—just the comments, not any indication of my ranking. This part was tough. I had eight reviewers, and while some were very positive, others were critical. The negative comments were hard to digest, but in hindsight, they provided valuable insights for improving the project, whether or not I was successful in this round.

Then one morning, I received the long-awaited email. I had been waiting nearly a year since I first started drafting my proposal, and the anticipation was overwhelming. My heart raced as I opened the email and read the first lines:

“Following the Step 2 panel meetings of the ERC-2019-COG call, the review panels have concluded their work and identified proposals to be recommended for funding for this call. We are pleased to inform you that your proposal has been…”

I felt a surge of excitement—“we are pleased” means I got it, right? Or…?

“…retained on a reserve list for possible funding in this call, if additional budget becomes available and subject to confirmation by the ERC Scientific Council of the final ranked list of proposals recommended for funding in this call and finalization of the evaluation process by the ERC Executive Agency.”

Wait, what? What does that mean? I had never heard of this reserve list concept before. My excitement quickly turned into confusion and worry. I immediately started emailing colleagues who were familiar with the ERC process to get clarification.

The Reserve List:

It turned out that being on the reserve list means that while my project had been approved, there wasn't enough funding available at the time. The ERC allocates a budget and funds the highest-rated projects within that budget. Those projects that are highly rated but not funded immediately are placed on the reserve list. So, while my project was essentially approved, I had to wait for additional funding to become available. I was told that in most cases, the ERC president finds a way to fund at least one or two projects from the reserve list, so I still had hope.

But that meant I could be waiting for up to a year for the final decision—talk about torture! Despite the uncertainty, I was still happy because my project had essentially been approved, so all the hard work wasn’t for nothing.

The Wait Continues:

Three weeks later, I received another email saying that the ERC was preparing my project documents. It was a huge relief! Later, I learned I was actually first on the waiting list, which gave me even more hope. Finally, after over a year of hard work and anticipation, I was officially funded.

Reflecting on the Process:

Looking back, the entire process took over a year, but it was an incredibly rewarding experience. The oral exam, in particular, was great—it gave me a chance to defend my ideas and ambitions in front of an esteemed panel of scientists. I loved the process of refining my presentation and engaging with the panel members, even though the waiting period (especially for reserve list projects) was nerve-wracking.

I hope sharing these personal details helps you prepare for your own ERC application. It’s a long and intense journey, but with preparation, hard work, and dedication, it’s entirely possible to succeed.